The Demographic Cliff: How Aging Societies Will Change Growth and Policy

Contents

- Slower Growth & Lower Potential

- Fiscal Strains and Shrinking Policy Space

- Effects on Global Trade and Capital Flows

- Inflation or Deflation?

- Policy Options: How Can Policymakers Build Bridges Across the Cliff?

- Microeconomic Realities

- Beyond the Cliff

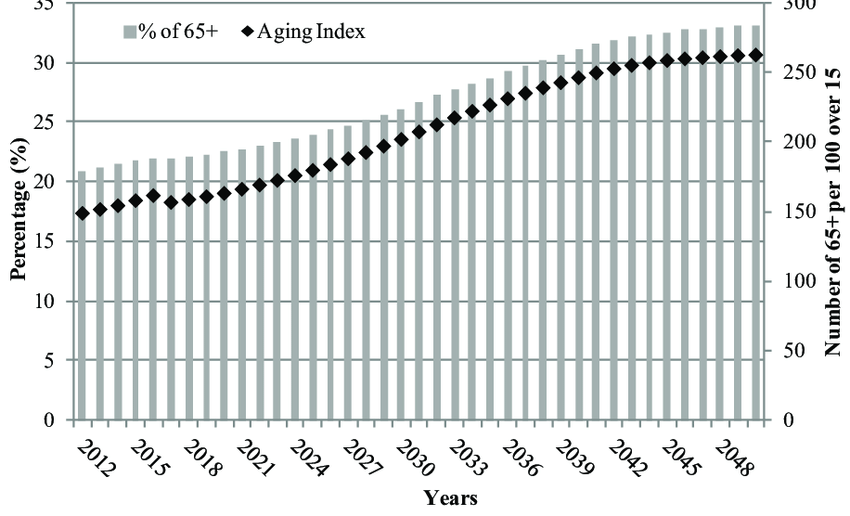

Societies are aging. And the elderly begin to retire—leaving hundreds of thousands of job vacancies in countries across the world. The labor force is weakening with no one to fill in the empty space left behind in the wake of a rapidly retiring population. Today, we will cover what the implications of this demographic cliff are, on a macro and micro scale.

Slower Growth & Lower Potential

To be frank, it wouldn't be far fetched to classify it as an impending disaster. One of the clearest findings in the demographic-economics literature is that aging can drag on per capita output growth. A seminal study by Mestas et al.(2016) finds that even in post-industrial countries like the US, a 10 percent point increase in the share of population over 60 leads to a decrease per capita GDP by 5.5%.

In other words, even without a full-blown collapse, countries drift into lower growth equilibria. And it's already happening. Japan has grown at an average annual rate of just 0.8% since 2000. Fertility rates in South Korea and many European states have fallen below 1.3 children per women, far beneath the replacement levels. As these trends continue to grow, the global labor pool will continue to contract, and the structure of economic growth will shift.

Fiscal Strains and Shrinking Policy Space

Aging erodes the potency of fiscal policy and public finances. Pensions and healthcare systems that are designed for economies with shorter & smaller retirees and large working populations are becoming unsustainable. The European Central Bank projects that by 2050, Europe's age-related public spending will rise by 4-5 percent of GDP, while tax revenues stagnate

Honda & Miyamoto(2021) finds that demographic aging "weakens the effectiveness of fiscal policy in boosting an economy." Fiscal policy is losing its effectiveness. Increases in government spending outputs less utility because older households save more and spend less. In application, this means that when the next recession/depression occurs, aged economies may find traditional stimulus tools blunt and ineffective.

Effects on Global Trade and Capital Flows

The effects of the demographic cliff spread beyond the domestic economy. It reshapes the global trade and capital flows in profound ways.

Börsch-Supan et al. (2001) shows that aged economies become net capital exporters.

Net Capital Exporters - A country that has more capital available from savings that it can profitably invest within its own borders, which in turn, leads investors to send their money elsewhere for better returns

This creates a two-speed world economy. On one lane holds an aging, capital-rich nation and younger, labor-abundant nations on the other. The former depending on returns from abroad; the latter relying on foreign investment and demand from aging consumers. Sounds like a great deal right? Not at all. This scenario creates a perilous and fragile equilibrium: if either side falters, global imbalances deepen, intensifying inequality and geopolitical tension.

Inflation or Deflation?

There are disagreements on whether aging is inflationary or deflationary. Empirically, Japan's "lost decades" shows deflation: retirees consuming less lowers aggregate demand. But in the modern economy, there are more strings to the picture.

Labor shortages, healthcare and eldercare costs surging, etc. will be key drivers of inflationary fiscal pressure through the 2030s. Arguably, simultaneous deflationary and inflationary forces will shift inflation in unpredictable directions.

Policy Options: How Can Policymakers Build Bridges Across the Cliff?

If aging is inevitable, the question is how to adapt. Economists and policymakers have proposed several strategies:

- Raise the Effective Retirement Age

Many OECD(Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries are gradually increasing retirement ages to reflect longer life expectancy. This alone could stabilize pension systems and ease labor shortages. - Invest in Automation and AI

As labor becomes scarce, productivity growth must do the heavy lifting. Japan and South Korea have shown that robotics can offset demographic decline if supported by education and retraining. - Encourage Immigration and Inclusion

Targeted immigration, particularly of younger skilled workers, can soften the demographic blow. At the same time, integrating underutilized groups, especially women and older workers, can expand labor supply. - Rethink Fiscal Policy

Governments may need to shift from payroll-based taxes (which shrink with the workforce) toward consumption and wealth taxes. Building fiscal buffers now will be crucial before dependency ratios spike. - Redefine Economic Success

As growth slows, policymakers may need to prioritize quality over quantity: focusing on health, sustainability, and intergenerational equity rather than headline GDP or other economic aggregates alone.

Microeconomic Realities

The shift in population age will reshape everyday life. While households save more for longer retirements and spend more on healthcare, younger generations may face heavier tax burdens and fewer job openings.

Firms will need to adapt to multigenerational workforces, redesign for flexibility, and innovate for the aging consumer. This "silver economy", comprised of goods/services tailored for the elderly, is projected to exceed $15 trillion globally by 2035.

Beyond the Cliff

It may be tempting to view this as a slow-motion catastrophe. Yet, this is all theory. According to Bradshaw and McDermott(2025), there is no iron law that older societies must stagnate; those that invest in innovation, education, and institutional quality can continue to prosper.

The real challenge is not how to avoid the cliff, but build a bridge across it. Through innovation, I firmly believe that societies can turn demographic aging from an impending crisis to a golden opportunity.

References:

- Maestas, N., Mullen, K. J., & Powell, D. (2016). The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force and Productivity. NBER Working Paper No. 22452.

- Honda, J., et al. (2021). Would Population Aging Change the Output Effects of Government Spending? IMF Working Paper WP/21/92.

- European Central Bank (2024). Demographic Change and the Macroeconomy. Occasional Paper No. 296.

- Börsch-Supan, A., Ludwig, A., & Winter, J. (2001). Aging and International Capital Flows. NBER Working Paper No. 8553.

- Bradshaw, T., & McDermott, M. (2025). Aging Without Collapse: Institutional Resilience and Economic Performance. arXiv:2508.16872.

- Warner, S., et al. (2025). Rethinking Demographic Transition. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society.